Gisela Probst-Effah

The Song of the Peat Bog Soldiers – Metamorphoses of a Song

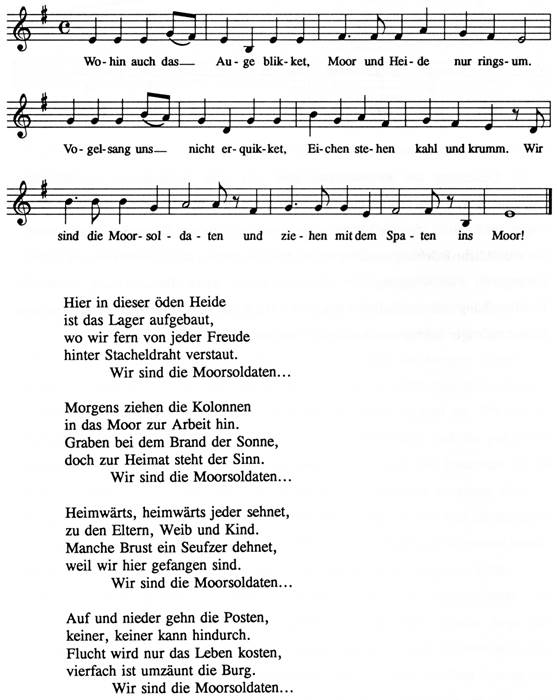

Die Moorsoldaten (original version)[1]

Song of the Peat Bog Soldiers[2]

Far and wide as the eye can wander,

Heath and bog are everywhere.

Not a bird sings out to cheer us,

Oaks are standing bare and gaunt.

We are the peat bog soldiers

We're marching with our spades

To the bog [moor].

[Here in this desolate moorland the camp is built,

Where we live without any joy behind barbed wire.]

[In the morning the crews go to work in the

bog,

where they dig, while the sun burns like fire, but they think of their home.]

[Homewards, homewards everybody longs for the parents, the wife and the children.

And we moan, because we are imprisoned.]

Up and down the guards are pacing,

No one, no one can get (go) through.

Flight would mean a sure death facing,

Guns and barbed wire greet our view

We are the peat bog soldiers [...]

But for us there is no complaining,

Winter will in time be passed.

One day we will cry rejoicing:

Homeland, dear, you're mine at last!

March no more with their spades

To the bog [moor].

The Song of the Peat Bog Soldiers during the “Third Reich”

Since the seventies the Institut für Musikalische Volkskumde at the University of Cologne is concerned with a research project about the songs in the resistance against National Socialism. In this context, the role of music in the concentration camps became one of my main subjects. My special interest was directed to the most famous song among them: the Song of the Peat Bog Soldiers.This song originates in 1933 at the concentration camp Börgermoor at Papenburg in Northern Germany. Since the beginning of the National Socialist dictatorship there were arrested political opponents – in the majority Communists and Social Democrats. They called themselves peat bog soldiers, because they wanted to emphasize their equality with the paramilitary SS, which was armed with carbines.

In the period before the war it was the duty of the prisoners, to cultivate the vast moore. Day after day they had to work with primitive instruments and without the help of machines: Work in the concentration camps focused less on profit than the drudgery and destruction of human beings (Sofsky 1993, 193–199).

The Song of the Peat Bog Soldiers was written in the summer of 1933 on the occasion of a cultural event in the camp, called “Zirkus Konzentrazani”, which the prisoners produced in response to a pogrom night of drunken SS men. They intended to counter the primitive brutality of the SS with self-confidence and moral superiority (Langhoff 1978, 178/ 179).

The miner and working-class poet Johann Esser (1896–1971) composed six stanzas, to which the actor and stage manager Wolfgang Langhoff (1901–1966) gave their present shape. Rudi Goguel (1908–1976), a commercial clerk with musical training, invented a melody, which he harmonized for a four-part male choir.

The “Zirkus Konzentrazani” was held with the permission and in the presence of the camp commandant in the afternoon of August 27th in 1933. It was a mixture of music and dances, cabaret and clown numbers as well as artistic and sport performances. The event was not supposed only to entertain, but also to criticize secretly, but understandable for the prisoners the situation in the camp. The finale and highlight of the afternoon was the première of the Song of the Peat Bog Soldiers. Its impression on the prisoners is described as overwhelming (Lammel/ Hofmeyer 1962, 17; Langhoff 1978, 192). It is reported, that even the SS was much impressed by it, because they were dissatisfied with their isolated situation in the moor (Suhr/ Boldt 1985, S. 14 et sqq.).

In the following time the song was often forbidden, but nevertheless it circulated quickly in the National Socialist camps and prisons. Many copies of it were smuggled into the other camps (Langhoff 1978, 258). It was sung in Sachsenhausen and Buchenwald and even in extermination camps as Auschwitz (Fackler 2002, 20).

Despite its predominantly dark, sad character the song with its change of mood from the minor to the major key in the chorus and especially in the final stanza with its image of the passing winter expresses in an encrypted way hope and optimism. It is reported that the prisoners have sung the final chorus with a special emphasis (Eisler 1973, 277).

Especially the political prisoners, who were experienced in illegal existence, developed cultural forms and rituals, which gave them stability in a hostile environment. Secretly they organized political discussions, courses and cultural events. In many reports the Communists are described as the most active resistance group. Their power, says the journalist, scientist and member of the resistance against National Socialism Eugen Kogon (1903–1987), came from their ideological strength, their obedience to the party and their long camp experience (Kogon 1946, 283).

The Song of the Peat Bog Soldiers was part of those cultural activities, it often formed their culminating point and solemn conclusion. Heinz Junge, a former prisoner, whom I have interviewed in 1990, recalled, that they sang the song to strengthen the “fighting morale“ (Probst-Effah 1995, 51).[3] It was sung on special occasions: as a conclusion of evening entertainments, in secret ceremonies, for example when prisoners were released or when new ones arrived. In the early Emsland camps there was a welcome ceremony to encourage them after a vexatious procedure of the SS:

“Whereas the SS welcomed them with brutal, intimidating beatings, the prisoners developed an own welcoming ritual: When the exhausted newcomers crawled into their beds, they were welcomed with the softly sung Song of the Peat Bog Soldiers or another familiar labour song. After that an anonymous voice in the darkness informed them about possibilities to survive” (Suhr/ Boldt 1985, 41; translation: Probst-Effah). Heinz Junge remembers the strong impression, the Song of the Peat Bog Soldiers left on him after his deportation to Börgermoor in 1933: “We were tired to death, we were in trouble, in anxiety of the future. And then somebody sings the Song of the Peat Bog Soldiers. Can you imagine, how much it impressed us?” (Probst-Effah 1995, 51; translation: Probst-Effah).

The composer Hanns Eisler has characterized the song as “camouflaged revolutionary”. It is told, that the prisoners sang the final stanza with much emphasis (Eisler 1973, 277). A former prisoner from Buchenwald has described the effect of these verses: “They were not only sounds. This was hope, it became certitude! The song helped us, it gave us stability and confidence in the days of February 1938 in Buchenwald Concentration Camp” (Musik in Konzentrationslagern 1991, 67; translation: Probst-Effah). The optimism in the final stanza was based on the conviction of the prisoners, that the dark present period was a stage of history, which they will overcome, that they were not victims, but fighters (Buchenwald 1988, 111). This certitude was encouraging and it protected against feelings of isolation, hopelessness and demoralization.

Outside walls and barbed wire the song was hardly known in Germany in the years between 1933 to 1945. Abroad, however, it was primarily spread by exiles. After his release from concentration camp in 1934 Wolfgang Langhoff emigrated to Switzerland. In the following year his report “Die Moorsoldaten” (“The Peat Bog Soldiers”) appeared in Zurich. It describes his experiences in German prisons and concentration camps during thirteen months. The book also contains the Song of the Peat Bog Soldiers and its history. Langhoff did not tell the names of the authors, because he wanted to protect them from the persecutions of the Nazis. Shortly after its publication Langhoff’s report was translated into seven foreign languages (Langhoff 1978, 193/ 194).

***

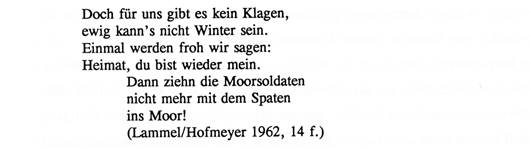

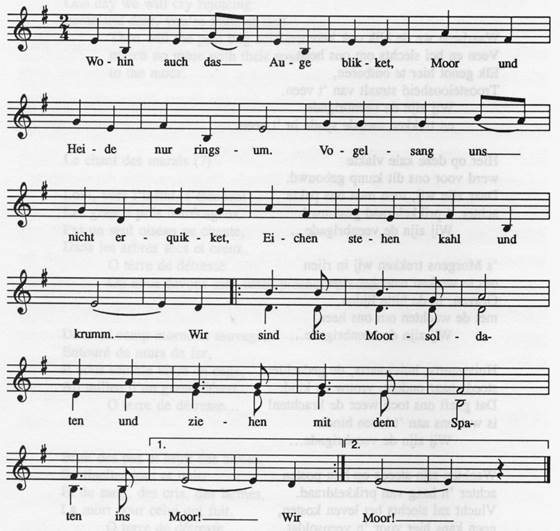

Die Moorsoldaten (Hanns Eisler’s version)

Rudi Goguel, the composer of the song, once emphasized the reference of the original melody to the situation in the camp Börgermoor: “The three invariable tones, with which the song begins, characterize the bleakness of the bog and the desolate situation, in which the peat bog soldiers had to live” (Lammel/ Hofmeyer 1962, 17; translation: Probst-Effah). The prisoners comprehended the simple, inconspicuous tone repetition at the beginning of the first and third verse as a concise musical expression of their misery. “It corresponded to the atmosphere in which we lived” (Der Moorsoldat 1978, 6; translation: Probst-Effah).

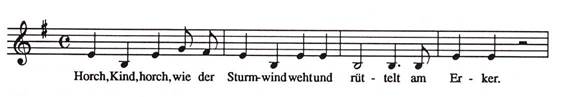

The symbolism of the tone repetition was probably unknown to Eisler, and maybe he had come to know the song in a version different from the original. In any case in the first bar of the song instead of the tone repetition there appears a fourth, which the composer now regards as highly important. In this interval he believes to find reminiscences of a song of the Thirty Years’ War with the text beginning “Horch, Kind, horch, wie der Sturmwind weht”, and in the change from the minor to the major key he supposes echoes of “the Russian revolutionary funeral march”[4] (Eisler 1973, 276).

By Hanns Eisler the famous actor and singer Ernst Busch (1900–1980) got to know the song. He took it to Spain, where it became part in the song repertory of the International Brigades during the Civil War (1936–1939). In 1937 Busch published the songbook “Canciones Internacionales de las Brigadas”, and at the front line a sound recording of “Six Songs for Democracy” was made – among them the Song of the Peat Bog Soldiers in a shortened version – presented by Ernst Busch and the choir of the XI. brigade.

***

An increasing local and temporal distance from the "original scene" in some cases caused transformations of the song. They also arose by the translation of the text into other languages, if literal translations were not singable and collided with the original metre of text and melody as well as the strict stanza pattern. Beyond that variants could be the results of adaptation processes: The form and the function of the song changed, when it was transferred into new contexts.

So the French adaptation of the “Song of the Peat Bog Soldiers” shows considerable divergences from the original: “Le Chant des Marais” was well-known in the French Résistance and beyond this it became popular in France. Since the beginning of the 1960s its refrain is carved in the stone of the Mémorial des Martyrs de la Déportation, which was erected on the Île de la Cité in the centre of Paris (DIZ Emslandlager 2002, supplement, 55).

Chant des Marais

Les grands prés marécageux

Pas un seul oiseau ne chante

Dans les arbres secs et creux.

Ô terre de détresse

Où nous pouvons sans cesse

Piocher.

Dans ce camps morne et sauvage

Entouré de murs de fer

Il nous semble de vivre en cage

Au milieu d’un grand désert.

Ô terre de détresse […]

Bruit des pas et bruit des armes

Sentinelles jour et nuit

Et du sang, des cris, des larmes

La mort pour celui qui fuit.

Ô terre de détresse […]

Mais un jour dans notre vie

Le printemps refleurira

Liberté, liberté chérie

[libre alors, ô ma patrie]

Je dirai: tu es à moi

Ô terre enfin libre

Où nous pourrons revivre

[Où nous pourrons sans cesse]

Aimer.

(DIZ Emslandlager 2002, supplement, 56)

Song of the Bogs[5]

Far to

infinity extend

The large marshy meadows

Not a single bird is singing

In the dry and hollow trees.

O land of distress

Where we can work constantly

with our picks.

In this bleak, wild camp

Surrounded by walls of iron

It seems to us to live in cage

In the middle of a desert.

Noise of footsteps and noise of weapons

Sentinels day and night

And blood, screams, tears

Death for those who flee.

But one day in our lives

Spring will blossom again

Freedom, freedom, darling,

[free then, o my homeland]

I say you are mine

Where we can relive

[Where we can ever]

Love.

In the French version only the desolate scenery reminds of the concentration camp Börgermoor, whereas the reference to the hard labour of the prisoners in the bog has almost vanished. The connection with the prisoners’ activity in the moor and their tools, the spades or picks, is indicated only vaguely in the refrain ("piocher" = to work with the pick). This modification of perspective corresponds to a fundamental functional and semantic change of the song: In the French version the prisoners appear only shadowy as suffering victims of persecution („du sang, des cris, des larmes“). The original character of the song, however, is militant. Heinz Junge remembers, that the prisoners called themselves “peat bog soldiers”, because they wanted to emphasize, that they had the same rank as the SS, who was armed. They carried the spades, which they needed for their hard work, on their shoulders – like guns (interview Junge, 6.7.1990). Heinz Junge remembers the following practice at Börgermoor: When they sang “Dann ziehn die Moorsoldaten nicht mehr mit dem Spaten” (“Then will the peat bog soldiers march no more with their spades”) they stamped their feet. This sounded very effective on the wooden floors in the barracks (interview Junge, 6.7.1990). In the prisonders’ imagination the secret resistant meaning of the last stanza sometimes increased to violence against the oppressors. Eugen Kogon remembers a text version of the final chorus, which circulated secretly in Buchenwald concentration camp: „Dann zieh’n die Moorsoldaten/ Gewehre statt der Spaten…“ (“Then will the peat bog soldiers march with rifles instead of spades…”) (Kogon 1974, 106).

Compared with the original refrain the French version does not have an aggressive, but a melancholic and moanful character, and the utopia of the final refrain appears as an intact, peaceful contrast to the camp reality. The character of a funeral song is expressed in several interpretations of the Chant des Marais, for example with the Swiss singer Michael von der Heide, which was recorded in 1996.[6]

The Song of the Peat Bog Soldiers after 1945

After 1945 the song was exploited in the Cold War between Eastern and and Western Germany. With the political division of the country it came into the area of conflict of the Western and Eastern ideologies.Rudi Goguel once said that the song had found its home in the German Democratic Republic, “where the legacy of the antifascist resistance had become a social reality” (Goguel 1973, 279; translation: Probst-Effah). The GDR, where after a long period of suffering many communists found their political home, considered to be the legitimate successor of the “antifascist” musical tradition. Since the early fifties, the Department of Labour Songs in the Section Music of the East German Academy of the Arts, published the series “Das Lied – im Kampf geboren” (“Song – Born in Struggle”). It includes “Lieder aus den faschistischen Konzentrationslagern” (“Songs from the Fascist Concentration Camps”), published in 1962 by Inge Lammel und Günter Hofmeyer.

In the GDR the Song of the Peat Bog Soldiers belonged to the officially sponsored and maintained vocal repertory. In schools, it was part of a compulsory program. In class 6 it was one of the songs, which pupils had to learn by heart (Lehrplan Musik 1971, 16). A former student recalls, that in school the song had almost the importance of Goethe's Faust (DIZ Emslandlager 2002, supplement, 5).

In the song research of the GDR the Song of the Peat Bog Soldiers belonged to the category “labour song”, which the musicologist Inge Lammel defined as “an instrument of the struggle of the working class against the capitalist power system” (Lammel 1975, 13; translation: Probst-Effah) – i.e. as part of a historical era, which extends over the long period between the beginning of the industrial revolution in the forties of the 19th century to the present time. According to this definition the combative function of the Song of the Peat Bog Soldiers was not limited to the period of National Socialism, because this was only the fatal culmination of the long capitalist aberration.

In this interpretation the role of the song within the socialist system differed fundamentally, as Inge Lammel points out: “The labour songs are no longer the weapon of an oppressed class against a class of exploiters, they are no longer in opposition to the ruling class; on the contrary they express the common interests of the party, the government and the working population” (Lammel 1978, 141; translation: Probst-Effah).

In this opinion the labour songs did not manifest present conflicts in the own country, but the struggles of the past; the present conflicts only within the political opponents’ sphere of influence. The resistance of the Song of the Peat Bog Soldiers was directed only against the fascist violence of capitalism; within the socialist countries, however, the song served as a monument of a past period, which was overcome, and as an affirmation of the existing political system.

In this sense it is interpreted on a recording from 1969[7]: as a grand arrangement for baritone solo, choir and orchestra. In this version the song no longer appears as an expression of the struggle for survival, but it has ascended into the sphere of state representational art. Another arrangement for a cappella choir on a recording from 1956 resembles ceremonial church music. Following the example of protestant chorale arrangements the melody forms the cantus firmus, which is paraphrased by the contrapuntal figurations of the other voices.[8]

***

In 1950 the Association of the Victims of Nazi Persecution published a collection of ten camp songs, among them the Song of the Peat Bog Soldiers (Lammel/ Hofmeyer 1962, 8). One year later it appeared in a song collection of the German Trade Union (Unsere Lieder 1955, 10). The short commentary attached to it doesn’t mention the authors and gives only a vague reference to its origin: “Aus einem deutschen Konzentrationslager” (“From a German concentration camp”). It seems remarkable, that only a few years after the decline of the Nazi era the publishers, members of the trade union, which had been persecuted by the National Socialists, did not know any more about the song. Has the ignorance been intentional?

In music school-books the song can be found since the mid-seventies. In 1979 it was published in a textbook for the lower secondary school. The comment attached to it is reminiscent of the Nazi crimes against the “dissidents, Jews and Christians, Democrats and Communists” (Musikunterricht Sekundarstufe I 1979/ 1980; translation: Probst-Effah): It seems not to be by incident, that the authors of the song – communists – are mentioned last. In comparison with the GDR in the Federal Republic the historical as well as the current function often was expanded: It is not only a song against fascist violence, but “against any kind of despotism” (Banjo 1979, 57; translation: Probst-Effah). In another textbook, published in 1996, the song appears under the headline “Lieder zum Nachdenken” (“Songs for Reflecting”). It is embedded in a very varied national and international repertory, which in many ways refers to the subjects war, struggle, death, violence, oppression, poverty, old age, loneliness etc. (333 Lieder 1996, 262). Under a common title there are presented very different songs: such as the French, English and German national anthem, The Song of Mackie Messer from the “Threepenny Opera” of Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill, “Lady in Black” of the rock group “Uriah Heep”, Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” and Ludwig van Beethoven’s “Freude, schöner Götterfunken”, which was popularized by Miguel Ríos’ “Song of Joy”.

In spite of those efforts, to rid the song of ideological connotations of the GDR, negative prejudices predominated. What the Eastern state and the government encouraged and supported, caused an instinctive distrust and rejection in the West. Even in 1980, the schoolbook “Banjo” first was not allowed by the Minister of Culture of Baden-Wuerttemberg. The objection was justified with the song selection. Especially the Song of the Peat Bog Soldiers, which the ministry characterized as a “compulsory antifascist song of the GDR” (“antifaschistisches Pflichtlied der DDR“), gave offence.[9]

At that time in the Federal Republic the song, however, had already gained popularity, not within the cultural mainstream, but in a youth culture with politically oppositional impulses: At the end of the sixties the Folksong Movement began to spread under the international influence of the Protest Song Movement, which was connected with the Civil Rights Movement in the USA. In this context the Song of the Peat Bog Soldiers emerged in Western Germany. It was sung by Pete Seeger, one of the initiators of the international Folk Revival. When the song returned to Germany, many people supposed it to be an English or American song, and they were very much surprised to learn that it was of German origin. In 1982 the author of an article series in a music magazine remembered, that at the age of eighteen years he came to know the song – not in German language, but in the English translation: “’We are the peat bog soldiers’ first impressed me by its melody without that I knew at that time, what the song means and that it was originally German” (Kühn 1982, 66; translation: Probst-Effah). Since the seventies the song belonged to the standard repertory of the Western German Folksong Movement, and its popularity grew more and more beyond this scene. Nowadays the Song of the Peat Bog Soldiers exists in many different musical interpretations and styles, even in jazz and rock adaptations.

Literature

Banjo. Musik 7–10 (1979). Ed. by Dieter Clauß et al. Stuttgart.

Buchenwald: ein Konzentrationslager. Bericht der ehemaligen Häftlinge Emil Carlebach et al. 2. ed. Berlin 1988.

DIZ (Dokumentations- und Informationszentrum) Emslandlager (ed.) (2002): Das Lied der Moorsoldaten 1933 bis 2000. Bearbeitungen – Nutzungen – Nachwirkungen. Papenburg. 2 CDs, supplement.

333 Lieder zum Singen, Spielen und Tanzen für die Sekundarstufe an allgemein bildenden Schulen (1996). Ed. by Hans-Peter Banholzer, Harald Hepfer, Wolfgang Koperski u. Klaus Wolf. Stuttgart et al.

Eisler, Hanns (1973): Bericht über die Entstehung eines Arbeiterliedes. In: Hanns Eisler. Schriften I. Musik und Politik 1924–1948. Ed. by Günter Mayer. München. 274–280.

Fackler, Guido (2000): Des Lagers Stimme. Musik im KZ. Alltag und Häftlingskultur in den Konzentrationslagern 1933 bis 1936. Mit einer Darstellung der weiteren Entwicklung bis 1945 und einer Biblio-/ Mediographie. Bremen (DIZ-Schriften. Vol. 11).

Fackler, Guido (2002): Zirkus Konzentrazani und Moorsoldatenlied. Kulturelle Selbstbehauptung im KZ. In: DIZ Emslandlager (ed.): Das Lied der Moorsoldaten 1933 bis 2000. Bearbeitungen – Nutzungen – Nachwirkungen. Papenburg. Supplement, 9–25.

Goguel, Rudi (1973): Gedanken zum Lied der Moorsoldaten. In: Intersongs. Festival des politischen Liedes. Ed. by Sieglinde Mierau. Berlin (GDR). 274–279.

Kogon, Eugen (1946/ 1974): Der SS-Staat. Das System der deutschen Konzentrationslager. Neuauflage Stuttgart, Hamburg, München (1st ed. Berlin 1946).

Kühn, Peter (1982): Wenn die Soldaten... Part 6: Antimilitaristische Lieder nach 1945. In: FOLKmagazin 5. 66.

Lammel, Inge (1978): Kampfgefährte – unser Lied. Berlin (GDR).

Lammel, Inge (1975): Das Arbeiterlied. Leipzig.

Lammel, Inge/ Hofmeyer, Günter (Hg.) (1962): Lieder aus den faschistischen Konzentrationslagern. Leipzig (Das Lied – im Kampf geboren. Vol. 7).

Langhoff, Wolfgang (1978): Die Moorsoldaten. 13 Monate Konzentrationslager. Stuttgart (1st ed. Zürich 1935).

Lehrplan Musik Klassen 5 bis 10 (1971). Ed. by Ministerium für Volksbildung (GDR). Berlin.

Mall, Volker (1979): Lied im Unterricht: Die Moorsoldaten. In: Musik und Bildung 11. 686–690.

Der Moorsoldat (1956 et sqq.). Ed. by Komitee der Moorsoldaten.

Musik in Konzentrationslagern (1991). Dokumentation der Tagung Freiburg im Breisgau Oktober – Dezember 1991. Ed. by Projektgruppe Musik in Konzentrationslagern. Freiburg i. Br.

Musikunterricht Sekundarstufe I (1979). Bd. 1. Schülerband. Hg. von Günther Noll, Hermann Rauhe, Ulrike Schaz. Mainz et al.

Musikunterricht Sekundarstufe I (1980). Lehrerband. Bd. 1. Hg. von Günter Kleinen, Heinz Meyer, Günther Noll, Hermann Rauhe, Christiane Schultz, Helmut Tschache. Mainz et al.

Probst-Effah, Gisela (1995): Lieder gegen „das Dunkel in den Köpfen“. Untersuchungen zur Folkbewegung in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Essen (Musikalische Volkskunde – Materialien und Analysen. Vol. 12).

Probst-Effah, Gisela (1995): Das Moorsoldatenlied. In: Jahrbuch für Volksliedforschung 40. 75–83.

Probst-Effah, Gisela (2007): Das Moorsoldatenlied. Zur Geschichte eines Liedes von säkularer Bedeutung. In: Good-bye memories? Lieder im Generationengedächtnis des 20. Jahrhunderts. Ed. by Barbara Stambolis/ Jürgen Reulecke. Essen. 155–173.

Probst-Effah, Gisela (2006): Das Moorsoldatenlied im Spannungsfeld deutsch-deutscher Ideologien nach 1945. In: Musik als Kunst, Wissenschaft, Lehre. Festschrift Wilhelm Schepping zum 75. Geburtstag. Ed. by Günther Noll, Gisela Probst-Effah, Reinhard Schneider. Münster. 384–399.

Probst-Effah, Gisela (2009): Streifzüge durch die „Biographie“ eines KZ-Liedes. In: Ewigi Liäbi. Singen bleibt populär. Tagung Populäre Lieder. Kulturwissenschaftliche Perspektiven 5./6. Oktober 2007 in Basel. Hg. v. Walter Leimgruber, Alfred Messerli und Karoline Oehme. Münster u.a. (= culture. Schweizer Beiträge zur Kulturwissenschaft, Bd. 2). 121-136.

Sofsky, Wolfgang (1993): Die Ordnung des Terrors: das Konzentrationslager. Frankfurt am Main.

Suhr, Elke/ Boldt, Werner (1985): Lager im Emsland 1933–1945. Geschichte und Gedenken. Oldenburg.

Unsere Lieder (1955). Lieder der Gewerkschaftsjugend. Ed. by Hauptabteilung Jugend im Bundesvorstand des DGB in cooperation with J. Heer, E.-L. von Knorr; J. Rohwer, W. Träder. 3rd ed. (1st ed. 1951).

© Gisela Probst-Effah

[1] Lammel, Inge, Günter Hofmeyer (Hg.): Lieder aus den faschistischen Konzentrationslagern. Leipzig 1962 (Das Lied – im Kampf geboren, Heft 7). 14/15.

[2] The English translation of the song (DIZ Emslandlager 2002, supplement, 33) consists only of three stanzas, which correspond to the first, fifth and the last stanza of the German original. In the following text I have tried to give the general meaning of the other three stanzas in English language.

[3] Interview Heinz Junge, 6.7.1990 at Dortmund (Probst-Effah 1995, 49 et sqq)

[4] “Unsterbliche Opfer“ („Вы жертвою пали”), text: W.G. Archangelski/ Hermann Scherchen.